/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/tgam/33UGCP3ADVP3XOZOFFWRZO7MUY.JPG)

A sign marks the headquarters of Moderna Therapeutics in Cambridge, Mass., on May 18, 2020.

Brian Snyder/Reuters

Canada will be among the first countries to receive vaccine shipments from Moderna, the biotechnology company’s chief medical officer said Monday, amid questions about how quickly the country will be able to administer COVID-19 vaccines to Canadians.

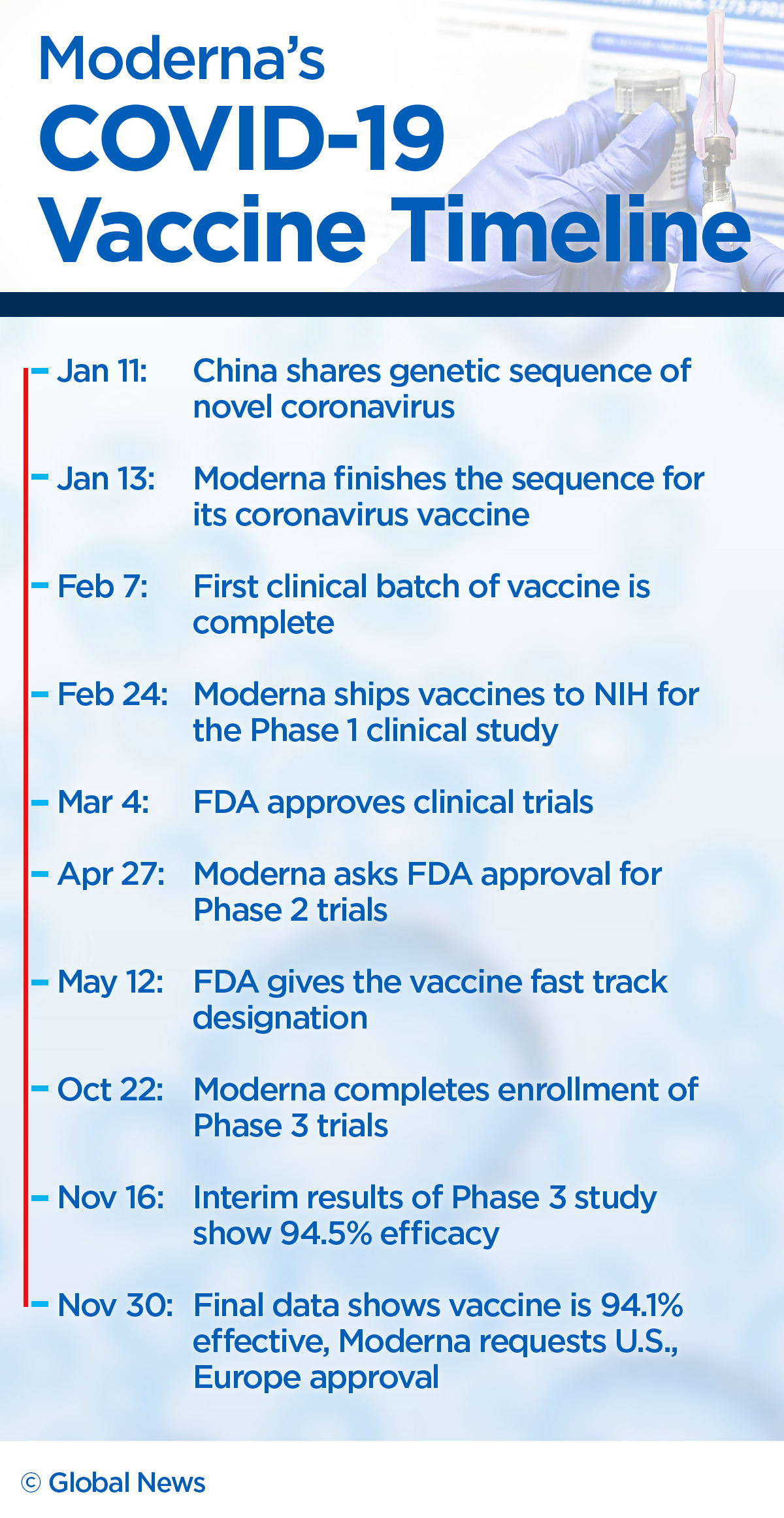

U.S.-based Moderna also announced Monday it is seeking approval for emergency use of its vaccine from U.S. and European regulators. But it is yet unknown how long it may take for Health Canada to approve Moderna’s vaccine and other COVID-19 vaccines that the federal government has ordered.

Tal Zaks, Moderna’s chief medical officer, told The Globe and Mail that Canada would receive doses from the company’s first batches of vaccines, and he anticipated the country would receive larger shipments by the early part of 2021.

“I’m hopeful that you’ll see significant quantities coming to Canada [in the] first, second quarter of next year,” he said. “Those first batches are going to be initially small and it’s going to take some time as we ramp up and accelerate our global manufacturing capacity. But we’re going to do our best to supply this vaccine that has such a high efficacy to as many people as we can. Canada’s in the front row.”

Moderna is among the producers of leading vaccine candidates with which Canada has struck procurement agreements. Canada has agreed to buy 56 million doses from Moderna and 20 million from Pfizer. But questions about when and how these vaccines will be distributed to Canadians have sparked criticism of the federal government for falling behind other countries in producing detailed vaccine plans.

On Thursday, deputy chief public health officer Howard Njoo said that Ottawa was expecting a combined six-million doses from the two companies by March, pending approval by Health Canada. Since each vaccine is administered in two doses, that would be enough for three million Canadians.

In its primary efficacy analysis of its Phase 3 trial, Moderna said in a news release on Monday that based on 196 cases of COVID-19 among the 30,000 study participants, it estimated its vaccine was 94.1 per cent effective against COVID-19 and 100 per cent effective against severe illness. It also said it had identified no safety concerns to date.

The emergency use authorization that the company has applied for in the United States comes on the heels of a similar application by Pfizer. Officials at the U.S. Food and Drug Administration said that, if issued, this type of authorization is not the same as a regular approval and that the companies will be required to continue to study the performance and safety of their vaccines. Emergency use is generally only granted when it is determined that the benefits of providing the vaccine outweigh the risks. People in the U.S. who receive a vaccine under emergency authorization must be given a fact sheet that describes the investigational nature of the product and may choose to refuse it.

In Canada, both the Moderna and Pfizer vaccines are currently being considered under a rolling submission process that allows regulators to look at vaccine data while clinical trials are still in progress.

That way, “we can start the review with the hopes that that would help find some efficiencies in the overall process,” Supriya Sharma, a chief medical adviser at Health Canada, told The Globe.

Steven Hoffman, director of the Global Strategy Lab and a professor of global health, law, and political science at Toronto’s York University, said the regulatory approval process is unlikely to present much of a hold-up in Canada. Instead, he said, the main issue will be how quickly companies can produce vaccines.

“Production is going to be the rate-limiting step,” Dr. Hoffman said.

Since the federal government placed orders for leading vaccine candidates at a relatively early stage, Canada should be in line with other rich countries to be the first to receive them, he said.

Dr. Hoffman said what is worrisome are the poorer countries, which have not been able to place vaccine orders and thus, will receive vaccines much later.

“That will end up creating inequities that will be felt in every country in the world because, of course, we live in a globally connected world,” he said. “So when some countries are left behind that ends up creating ripple effects that affect all of us.”

Joel Lexchin, an expert on pharmaceutical policy and professor emeritus in the faculty of health at York University, said it is important that Health Canada do its own reviews, instead of simply following the U.S. or European approvals.

By following its own approval process, “it can independently evaluate the information it is presented and perhaps come up with its own conclusions,” he said.

Sign up for the Coronavirus Update newsletter to read the day’s essential coronavirus news, features and explainers written by Globe reporters and editors.

https://news.google.com/__i/rss/rd/articles/CBMic2h0dHBzOi8vd3d3LnRoZWdsb2JlYW5kbWFpbC5jb20vY2FuYWRhL2FydGljbGUtY2FuYWRhLXdpbGwtYmUtYW1vbmctZmlyc3QtY291bnRyaWVzLXNldC10by1yZWNlaXZlLW1vZGVybmEtdmFjY2luZS_SAXdodHRwczovL3d3dy50aGVnbG9iZWFuZG1haWwuY29tL2FtcC9jYW5hZGEvYXJ0aWNsZS1jYW5hZGEtd2lsbC1iZS1hbW9uZy1maXJzdC1jb3VudHJpZXMtc2V0LXRvLXJlY2VpdmUtbW9kZXJuYS12YWNjaW5lLw?oc=5

2020-12-01 02:12:54Z

52781216634638