Real-world findings are starting to back expectations for the level of protection provided by several leading coronavirus vaccines, but there's still a burning question among scientists: Could the shots actually reduce virus transmission as well?

New research out of Israel offers early clues that at least one vaccine — the mRNA-based option from Pfizer-BioNTech, which is also being used here in Canada — may lead to lower viral loads, suggesting it might be harder for someone to spread the virus if they get infected post-vaccination.

In a study released publicly on Monday as an unpublished, non-peer-reviewed preprint, a team of researchers from the Israel Institute of Technology, Tel Aviv University and Maccabi Healthcare Services found the viral load was reduced four-fold for infections that occur 12 to 28 days after a first dose of the vaccine.

"These reduced viral loads hint to lower infectiousness, further contributing to vaccine impact on virus spread," the researchers wrote.

Virologist Jason Kindrachuk, an assistant professor in the department of medical microbiology at the University of Manitoba, said it's been a waiting game to figure out whether the protection from illness offered by mRNA vaccines might also curb transmission — a key tool for winding down the pandemic.

"So the data from this, I think, is important," he said. "It doesn't answer all the questions, but it starts to tell us that there actually might be some added benefit to these vaccines beyond just reducing severe disease."

Toronto-based infectious disease specialist Dr. Isaac Bogoch, a member of Ontario's vaccine task force, agreed these early findings — which still require peer-review — aren't a scientific "home run," but do offer hope in the fight against COVID-19.

"This would point in the direction that people who have been vaccinated, who are still infected, may be less likely to transmit starting at about 12 days after their vaccine," he said.

'Significantly reduced' viral loads

Israel is among the world leaders for COVID-19 vaccination rates, with Maccabi Healthcare Services vaccinating more than 650,000 people by Jan. 25, the paper noted, giving the researchers a large pool of data compared to what exists so far in many other countries.

The team analyzed COVID-19 test results from roughly 2,900 people between the ages of 16 and 89, comparing the cycle threshold values of post-vaccination infections after a first dose with those of positive tests from unvaccinated patients.

So, what are cycle threshold values, and how does that potentially tie to viral loads and virus transmission?

Standard polymerase chain reaction (PCR) tests for COVID-19 identify the viral infection by amplifying the virus's RNA until it hits a level where it can be detected by the test. Multiple rounds of amplification may be required — and the cycle threshold value refers to the number of rounds needed to spot the virus.

Have a question or something to say? CBC News is live in the comments now.

"If you can detect the virus with very few cycles, there's probably a lot of virus there," Bogoch explained. "If you need to keep looking and looking and looking and looking for it, it might be there — it's just a lot harder to find evidence of the virus genetic material."

A higher cycle threshold, then, usually means there's less virus genetic material present, which usually translates to people being less contagious, he said.

Based on an analysis comparing post-vaccination test results up to Day 11 to the unvaccinated control group, the Israeli researchers found "no significant difference" in the distribution of cycle threshold values for several viral genes.

That changed by 12 days after vaccination, with the team finding a "significant" increase in cycle thresholds up to 28 days later.

The result suggests infections occurring 12 days or longer following just one vaccine dose have "significantly reduced viral loads, potentially affecting viral shedding and contagiousness as well as severity of the disease," the team concluded.

It's a finding that appears to mimic the efficacy of the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine in its clinical trials, which offered some early protection starting 12 days after the first dose and fully kicks in a week after the second shot, with a reported efficacy of around 95 per cent.

More research needed, experts say

The observational study was not a randomized controlled trial — meaning researchers couldn't conclude a direct cause-and-effect relationship — and has not yet been published in a scientific journal. The research also has notable limitations, its authors acknowledged.

For one, the group of vaccinated individuals may differ in key ways from the demographically matched control group, such as their general health. The study also didn't account for variants of the virus that may be associated with different viral loads, the team wrote.

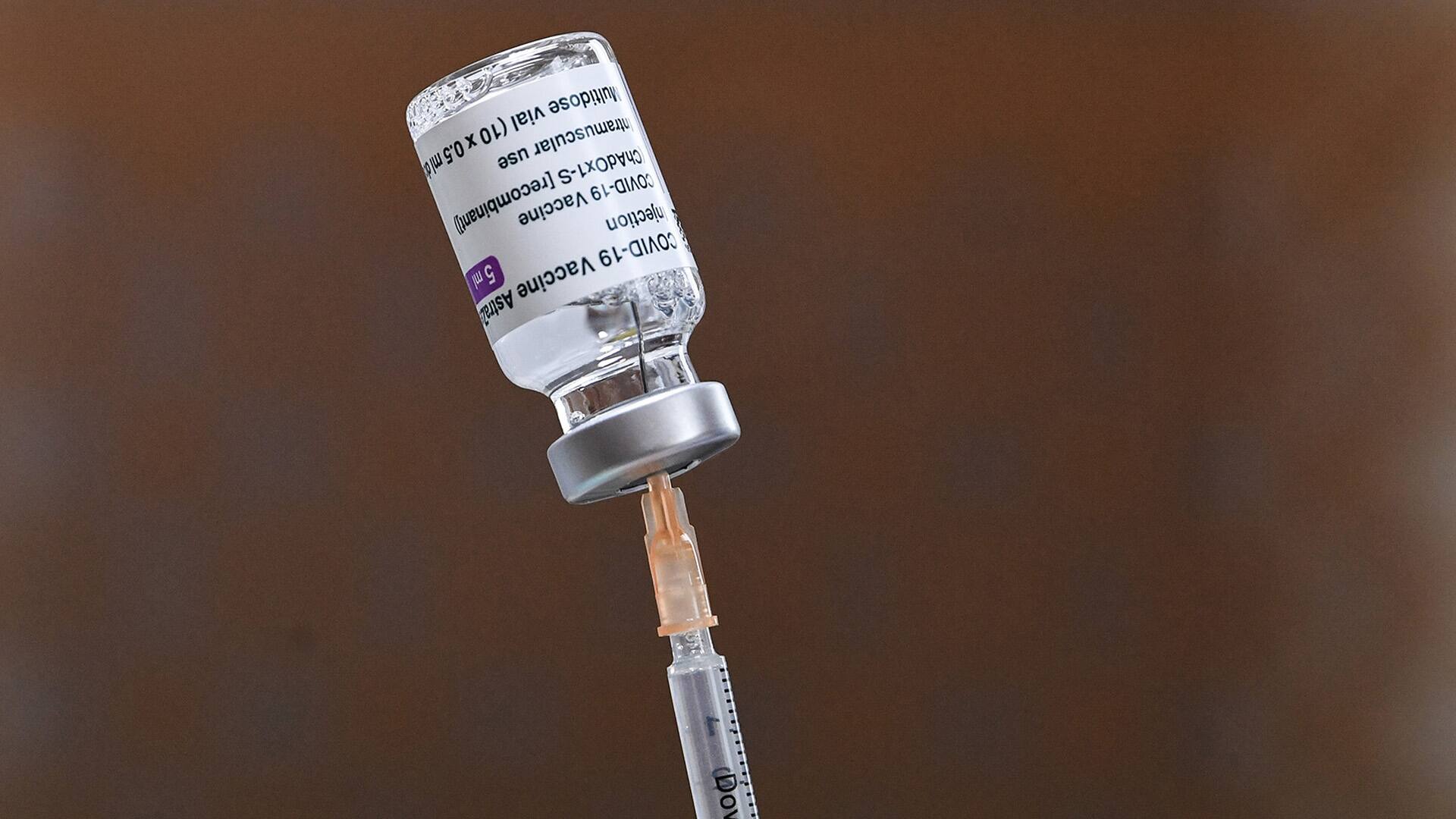

Indeed, those variants are already proving to be roadblocks in the fight against COVID-19, with concerns ranging from higher transmissibility to reduced vaccine efficacy, including concern in South Africa and beyond after a small and yet-to-be-published study suggested the Oxford-AstraZeneca vaccine offered minimal protection against mild infection from the country's now-dominant B1351 variant.

With those concerns in mind, experts who spoke with CBC News about the Israeli study stressed that more research is needed to back up the results on a broader scale, and among diverse populations, before being used to fuel policy changes or current approaches to vaccination efforts.

"The data needs to be reviewed by experts and confirmed that it stands up to the quality that we would want to make a conclusion," said vaccinologist Alyson Kelvin, an assistant professor at Dalhousie University in Halifax who works with Canadian vaccine developer VIDO-InterVac in Saskatoon.

WATCH | The impact of variants on the race to vaccinate:

Even so, Kelvin said the data appeared to be treated with the necessary caution, and offers "promising evidence," while Kindrachuk remains optimistic as well that the findings could prove a useful starting point.

"While we still have to have people using masks, and while we still have to have people distanced, the vaccines may actually also be able to reduce transmission," he said.

"So, those trends that we're hoping to see, in regards to trying to curb community transmission for SARS-CoV-2, may be accelerated with a vaccine — and that will hopefully help us get out of this a little bit sooner."

Have questions about this story? We're answering as many as we can in the comments.

The Current21:46Vaccine concerns in South Africa

https://news.google.com/__i/rss/rd/articles/CBMiSmh0dHBzOi8vd3d3LmNiYy5jYS9uZXdzL2hlYWx0aC9jb3ZpZC12YWNjaW5lLXRyYW5zbWlzc2lvbi1wZml6ZXItMS41OTA3NDU50gEgaHR0cHM6Ly93d3cuY2JjLmNhL2FtcC8xLjU5MDc0NTk?oc=5

2021-02-10 14:10:00Z

52781365730569

Tidak ada komentar:

Posting Komentar